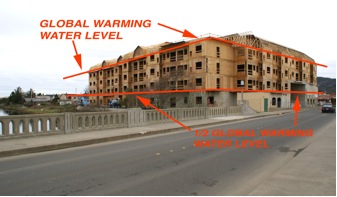

Current development standards still allow construction such as this, with its toes almost in the ocean even under normal conditions. Should we pay insurance for new development certain to be impacted by tsunami and global warming?

In 2006, some 600,000 homeowners living in coastal areas that insurers consider high storm risk saw their insurance policies cancelled or not renewed. This includes coastal areas stretching all along the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean from Texas to New York. Allstate Insurance totally pulled out of Florida, leaving 650,000 policy-holders without insurance. A 2007 study by Environmental Defense showed that new policies in Miami, Florida are now costing residents 500% more than previous ones. In March 2008, State Farm, the last major insurer in coastal coverage, pulled out. It no longer will write homeowner policies within a mile of the Atlantic Ocean.

Insured losses in the U.S. from tropical storms and hurricanes in 2005 alone surpassed $55 billion, while uninsured losses were estimated at another $37 billion. Currently, coastal properties in those areas are valued at $7.2 trillion, which represents an immense risk of loss. Global warming means even greater losses, particularly along low-lying coastal areas. Not just the Oregon Coast, but New York City, San Francisco, most of the state of Florida, and of course New Orleans again.

Even now, try to get a new homeowner’s insurance policy today on a home at the Oregon Coast. State Farm, which until recently wrote 40% of homeowner’s policies in Clatsop County, will no longer issue a new policy within 1000’ of the ocean. Allstate is discussing a policy ban within 2500’ of the ocean.

Many coastal states have had to become insurers of last resort – the so-called FAIR plans (Fair Access to Insurance Requirements). But critics rightfully complain that such insurance allows at-risk development to continue, creating greater hazard. Helping spread out the cost impact of disasters on existing investment is one thing. Blindly giving public subsidies to allow new construction with high probability of future losses is another issue – one it would seem wise to avoid.

As insurance underwriters vanish from coastal areas, who takes the risk and who pays for losses? Who’s going to bail us out? Even ranchers in Pendleton and farmers in Minnesota pay a share of the cost of “disaster” bailouts after the more intense storms that we are already beginning to experience. Just the uninsured losses from Katrina amounted to over $100 billion, and the losses from the Dec 7 storm on the Oregon and Washington Coast exceeded $165 million.

Who pays for the increased risk of new construction like this in areas known to be in high risk from tsunami or global warming?

Why let the situation get worse, and more costly? Allowing more development in impacted areas only means a deeper hole to get ourselves out of. Is it time for a moratorium on construction in very-high-risk areas? A moratorium isn’t permanent – you review when you know more. What better way is there to get people’s attention than to stop business-as-usual until we know what impacts are likely to be?

Projected sea level rise for global warming is around 47’. Allowing for high tides and storm tides pushes “buildable land” height to +60MSL. Coincidentally, that’s in a similar impact area now expected from tsunamis from offshore earthquakes that are expected to recur in the near future. The new tsunami inundation map recently released for Cannon Beach put virtually the entire city within the potential impact zone. Seaside faces relocating all of their schools out of impact zones, and Cannon Beach, which relocated its fire station to be in a safe area, now has to begin again.

It seems unavoidable that a third of this height will be devastated by tsunami or sea level rise. So a moratorium on new construction below +30’MSL would be a good, and very conservative, first step until we know more and have or haven’t taken strong action to reduce further impacts. Such a moratorium might allow uninsured placement of a single manufactured home on a parcel by existing owners, which could be relocated if needed.

Why should those who happen to live near the ocean take the financial brunt of the effects of everyone’s excessive use of fossil fuels? Why should the 150,000,000 people of Bangladesh, who lost 300,000 homes in a single 1998 flood, face flooding of their entire country because of wasteful fossil fuel use of wealthy countries and our lack of action to minimize global warming from it?

It’s time for responsibility, and for real action. Now. Any potentially-impacted jurisdiction can impose a moratorium like this. If Oregon wants to believe in itself as a leader in global warming issues, it’s time for the state to take action, not do more “studies”.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: The above commentary was written more than three years ago, but singularly omitted from the area newspaper written for. Its message rings louder and clearer today, after the Sendai tsunami and more recent research on earthquake/tsunami impacts here. What has yet to be addressed anywhere is what do we do AFTER a tsunami. Do we allow people to rebuild on vulnerable sites? There is no “300 year” guarantee of time between coastal subduction-quake-caused tsunami, or the amount of stored energy released each time. Seaside has taken a first step, in planning for school relocation/emergency shelter/estuary museum/commercial center on the highlands to begin to focus development above at-risk elevations. It’s time to go further.

Excellent post Tom! Well said and clearly reasoned.

The phrase “moral hazard” comes to mind, because I’ve heard economists and policy-makers use it (even if few seem to take it to heart). According to Wikipedia, a moral hazard occurs when one party makes a decision about how much risk to take, while another party bears the costs if things go badly, and the party insulated from risk behaves differently from how it would if it were fully exposed to the risk.

Those who profit from development in tsunami indundation zones should carry the risk. Unfortunately, on this front and elsewhere, our policy

makers are prone to privatize profits and socialize costs. The

consequences of this behavior were exposed in the mortgage-backed

tsunami and subsequent government bailout that wiped out our economy.

The fact that the mainstream press has sidelined this issue shows how hazardous our society has become.

The basic question is how to get from where we are to where we might like to go. While I appreciate the idea of not “digging deeper” hole, the fact of the matter is that our coastal communities depend on the close proximity of the ocean for their economic survival, whether it is tourism based activities or port based activities. A building moratorium will essentially disrupt local economies that are already hurting from the economic melt down. It doesn’t do much to help us get State or Federal help, and would actually be counterproductive by reducing the value of coastal property, thus making it less likely we would get the help.

Moving communities out of harm’s way has proved to be a very difficult thing to do and there are few examples of this in the US or elsewhere. There is one example in Oregon, the relocation of Arlington when the John Day Dam went in. This was for a small community and the resources of the Corps of Army Engineers was available. Not something that is replicable for the Oregon coast.

Even in Japan, where several communities decided on this approach after the Tohoku earthquake/tsunami, it has met with serious resistance and problems (such as the availability of buildable land, land ownership, need for proximity to the ocean, and attachment to “place”).

Adjustments are already happening, such as the relocation of the schools in Seaside, Cannon Beach, and Gearhart; and the school buyout of the Waldport school. These also bump up against Oregon’s land use zoning, which is geared to keeping schools within communities and compact urban growth boundaries. In the Waldport case, the school property must be changed to open space. This would be the requirement for school sites in Cannon Beach, Seaside and Gearhart, is FEMA money is involved. The Seaside School district is declining this approach, since they think they will get more money to relocate the schools from selling the property after rezoning. Thus a moratorium would be a detriment to relocating the schools to safe ground.

Current land use zoning is also a challenge. It is essentially static, assuming that the existing natural conditions are what they are when adopted by the state and local communities. As Cascadia and global warming show, we are actually in a dynamic natural environment, whether a catastrophic change such as the Cascadia earthquake/tsunami or a slow but steady change of global warming. Changing land use to reflect dynamic change will come slowly and will be a challenge for both the environmental and business communities.

It would be nice to think that the outside world would care about its impact on coastal communities, but for the moment a lot of dealing with this will fall on our own ideas and resources.