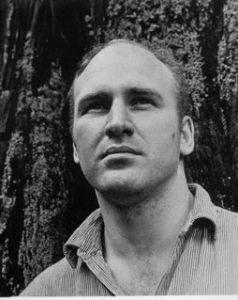

Ken Kesey, the man himself, loomed large during my Eugene years – an elder prankster, still generating a buzz and mild mischief around almost every worthwhile corner. To me, he seemed nearly as venerable, nearly as emblematic of the town’s gestalt and vibe, as the very university buildings that he ambled past – a man just as steeped in his place as the place was steeped in him. West of town, traveling down the Siuslaw to the coast, we often retraced the flow of his semi-fictional Wakonda Auga River, down to where the flat tidal water surged past an old white gothic house, perched with improbable defiance on the river’s bank; rumored to be the inspiration for the Stamper house, it seemed to be built along the river by people who chose not to go with its inexorable flow. Kesey himself drove that route often. His introduction to Sometimes a Great Notion incants its landmarks like a moss-draped dreamline.

At times the coast may have seemed sleepy and remote, full of what Kesey described as “towns dependent on what they are able to wrest from the sea in front of them and from the mountains behind, trapped between both. Towns all hamstrung by geographic economies…all so nearly alike that they might be nested one inside the other like hollow toys.” Yet, along his Siuslaw path, and downstream to the open coast, Kesey was witness to revolutions. Between the time when his family moved to Oregon in 1946 and when Sometimes a Great Notion was published in 1964, industrial capitalism and modernity’s full lurch remade the coast and shook the mountains fronting it, bringing convulsive and lasting changes to the people and the lands of the Oregon coast. Speaking through his Notion, Kesey would prove to be one of the most articulate eyewitnesses to that revolution. A deep reader of the addled landscape, he both learned from the spectacle and conjured sweeping narratives to give it a human face.

All small town museum hype aside, the cumulative effects of logging had remained modest prior to Kesey’s time. In spite of the awesome mechanical drama of logging, and its sepia-toned nostalgic weight, its effects were scarcely felt far from tidewater, where logs could be dropped right into the chuck and floated to mills and markets beyond. Driven by hand tools, and the muscles of men, oxen, and burly draft horses, pre-industrial logging would have been instantly recognizable to the loggers’ European ancestors, centuries before. Though my horse-logging ancestors might roll over in their soggy grey Northwestern graves to hear it, logging’s reach on the coast was very limited – limited, that is, until roughly the moment that young Ken Kesey arrived on this land.

Like most revolutions, this one had been years in the making. In the buildup, industrial engineers and detached-garage tinkerers had amassed a formidable arsenal. Through the 1920s and 1930s, welders and cutting torches transformed clunky World War I military surplus trucks into some of the region’s very first logging trucks, inspiring standard models in the years ahead. Commercial manufacture of the first portable chainsaws began at the same time, companies like Dolmar and Stihl wrapping up old gear-and-gas technological concepts in new, lightweight packages, the first to tree-cutting machines to be carried by hand to the woods. Yet, for years, these new tools of industrial forestry sat largely silent. The Great Depression and World War II had stalled everything, mothballing mills and sending working men out onto new and precarious paths. The technological transformation of the forest played out only after the War’s end, as America boomed with babies, suburban housing leapt and tumbled out from the nation’s cities toward the suburban fringe, and the cities of Europe and Asia arose from the carnage and rubble with American wood. In an instant, long-idled capital, and all of those stockpiled and silent machines, were unleashed upon the Oregon coast. From the moment that Kesey arrived, new logging roads of pit rock and dust scrawled brownish-grey across the lush and forested landscape, allowing machines to penetrate the forest, extending logging’s reach into every hollow and hill. The old trees fell even in remote places, as the protective embrace of distance fell away.

In the boom times, and in the bust that followed, logging companies came and went, making improbable demands on workers, and inspiring limited loyalties. Ruggedly individualistic gyppo loggers such as Notion’s Hank Stamper, with loose connections to many logging operations but loyalties to none, evolved and adapted from the primordial tumult of industrial logging, providing gyppos with a kind of economic resilience and longevity and freedom that was difficult for any “company man” to achieve.

No doubt about it: the same modernist impulses that reshaped the forest also reshaped the people. In Notion, “Indian Jenny” reminds us of those lessons too. At the time the Keseys came to Oregon, there were still tribal elders on the coast who remembered the whole terrible sweep of their history: people born into tribes that lived upright and sovereign in villages lining the shore, only to become minorities and refugees on their own lands, living on the fringes of new logging towns that sprang up abruptly, with machines that swallowed their natural heritage whole. By 1954, the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act brought the spirit of mechanization and uniformity to Native people too in a grand social experiment that toppled tribal governments along the entire coast, the Siletz and Grand Ronde, while closing the door soundly on federal acknowledgement efforts by others, such as the Siuslaw people lining the very coast Kesey described. Tribal members were cast adrift, while a few still lived in precarious isolation on the margins of a new Oregon coast culture. Indian Jenny was not a wholly fictional character. In recent years many tribal governments have been restored, but the ghosts of that time still lurk in their staid meeting rooms and spin like leaves behind the plush office furniture of the council chamber hall.

The coast Kesey described, and this convulsive moment in its history, has already come and gone. Tourist values and urban aesthetics rattle and remake the coast, fueled by cheap gas and sprawling new connectivities. The discordant drone and clang of old industry must now harmonize with new tunes, and a timbre set by the gentle consumption of scenery. Isolated little towns, once positioned like beads on the highway string, all encircled by ocean blue and forest green, now ooze out beyond their borders and connect – threatening to become a single, 363-mile-long strip development punctuated by a smattering of state parks and scenic vistas. The logging industry – its operations now automated, its labor force downsized time and again, its fate in the hands of office-tower brahmins and hedge fund sharks – also sprawls out into odd postmodern spaces unimaginable a half century ago. Big Timber lurches unpredictably in this direction and that, trying to remake itself and somehow wring next quarter’s profits from the distant Oregon woods.

Like Kesey’s protagonists, the land he described, this Oregon coast, is a rugged landscape that stands alone. The land still has its own identity today, though its shape falls in and out of focus, its boundaries and meanings increasingly contested. This land also has its own stories. No doubt, it deserves to have more. Interconnected with exponential intensity, and dependent on the outside world in countless ways, isolation falls away and we struggle in the rain to maintain our own, shared local lore. In time, Notion might prove to be one of our few points of mutual reference. The collision with industrial America and its mid-century machines forever transformed Oregon coast landscapes and Oregon coast cultures. In so many ways, they all burst fully onto the scene at a single pivotal moment, and it was Kesey’s moment. Sometimes a Great Notion is a rare, clear voice from that time. Listen up: if you want to understand where we were and where we are going, you must retrace his path. Pick up the book and let Kesey be your guide on his tumbling and visionary trip down the coast.

– First published in the printed Fall Equinox Edition 2014 of Upper Left Edge.

Leave a Reply