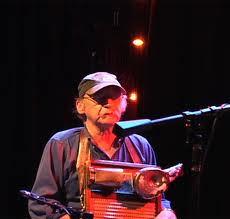

I first met Billy Hults in the fall of 2001. Or was it 2002? I don’t recall precisely and it hardly matters when it comes to writing a mini memoir of my unique relationship with Billy (although everyone had a unique relationship with him). Billy wouldn’t care either way about the veracity because he was an extraordinary fabulist in the Bob Dylan mold and often left the facts blowin’ in the wind.

Okay, it was 2001, after 9-11, when the government started treating radical environmentalists like a splinter group of Al Qaeda and handing down 25-year sentences for torching a couple of used cars or burning down a ski resort under construction.

The subject of our meeting was the Acey Line unit, a pristine parcel of old trees in the God’s Valley area of the Tillamook State Forest near Mohler off Highway 53. This idyllic section of forestland had escaped the ravages of the Tillamook Burn and represented one of the few naturally-seeded areas of the plantation that is the Tillamook State Forest. Naturally, the Oregon Department of (clearcut) Forestry (ODF) wanted it logged for a couple of dozen temporary jobs (not even local ones) and some meager tax receipts.

The proposed thinning drew the substantial ire of local and Portland conservationists, including one Tre Arrow of the Cascadia Forest Alliance. Tre was a notorious and radical environmental activist in those days and he desperately wanted to save Acey Line from the chainsaw. He constructed a platform near the top of one of the God’s Valley giants and raised the stakes of the protest. It was the first tree sit in an Oregon state forest and ODF and the Tillamook County Sheriff’s Office officials were clueless how to handle the controversy.

Billy took up the cause in the Upper Left Edge and on the ground and I began writing about it for the Astoria-based alternative monthly Hipfish and running supplies to the tree sitters.

At some point in the standoff, which lasted a couple months, a lackey acting under orders from the Tillamook County Sheriff either cut a branch out from under Arrow in the dead of night or he fell trying to leap to another branch. Or a little of both. Each side told a different version but the one sympathetic locals heard on police scanners and CB radio directly contradicted the official exculpatory tale from the Tillamook Sheriff’s Office. In other words, they might have lied. At the time I believed they had lied and said so in print.

After the thinning, ODF arranged a press tour of the site. About a dozen members of the print, television, and radio media showed up. They all represented well-known media outlets and held out impressive laminated press credentials for admission to the site.

It was at this media gathering in front of a metal gate blocking a logging road where I met Billy for the first time. When the press flack asked Billy what media outlet he represented, he told them and brandished a few copies for good measure.

The Flack said in so many words that the Upper Left Edge wasn’t legitimate enough (meaning not corporate) a publication to warrant access to the site. Hipfish wouldn’t cut it either.

Billy didn’t bat an eye and proceeded to give the flack a highly polished and brief lecture on the First Amendment and freedom of the press. The Flack had no authority to determine what qualified as a legitimate publication. If he didn’t let Billy pass, he’d be violating Billy’s Constitutional rights (and mine) and adding another unwanted twist to this controversy. Billy asked the flack, “You’re supposed to be solving problems, not creating them. That’s what public relations men do.”

The flack waited for a second and then Billy produced a crinkled 3 X 5 note card with the words “PRESS PASS” handwritten in black marker. He must have created it on the drive up, knowing something exactly like this would happen. He handed it to the flack and wordlessly walked me and another writer from some environmental publication right past the gate. I had a hard time not laughing. The flack didn’t say anything.

On site, Billy took notes, climbed over the downed trees, and took photographs. He asked the flack one tough question after another that really didn’t have much to do with logging. They were more existential in nature. The only one I firmly recall was, “Do you like doing this sort of thing for a living? Explaining why it’s okay to murder something beautiful.”

Later that year, I was called for jury duty in Tillamook County where I lived at the time. After the voir dire process (which I passed), a judge asked prospective jurors if there was any reason they couldn’t serve without bias.

I raised my hand and said, “Your honor, I can’t possibly serve on a jury where any deputy of the sheriff’s department testifies. I wouldn’t believe a word he says.”

Everything instantly came to a halt in the courtroom.

“Why?” the judge said.

“I was involved in the God’s Valley protests.”

“You’re excused.”

I got up from the jury box and walked out of the courtroom.

In the following years, Billy and I became good friends and he published a couple of my polemics in the Upper Left Edge. Later, when I got the book writing going, I published two of Billy’s essays, one about his unlikely connection to the Portland Trail Blazers’ vegetarian bad ass forward Maurice Lucas, and the other about the legendary Mayor’s Ball, an unprecedented event staged at Memorial Coliseum to retire newly elected Bud Clark’s campaign debt. The Mayor’s Ball was a seminal rock and roll quasi political circus that I consider as one of the crucial events in modern Portland history and the precise date the Rose City became officially unofficially weird.

Naturally, Billy masterminded the Mayor’s Ball, as he did so many other schemes for sundry good causes.

I dearly miss those schemes. They made Oregon a lot more interesting place to live. You know how I suggest we honor Billy Hults on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of Jupiter Books? Conjure a scheme for good; implement it on a lark.

Leave a Reply