Back in 1986, I was browsing my university bookstore when someone yelled, “How dare you wear that?!” Before I turned around, I glanced down to make sure my pants matched my shirt. What could I be wearing that was so offensive? Was this hostility even directed at me?

The scowling woman was dressed in a black skirt that skimmed her ankles, a long-sleeved blouse buttoned up to her chin, and a Star of David pendant. She must’ve been the Jesuit university’s only Orthodox Jewish student, and here I was, a woman in a kippah (better known by its Yiddish name, a yarmulke)—in her tradition, religious headgear reserved for men.

“I plan to go to rabbinical school after I graduate,” I stammered. “Um, in my denomination, it’s acceptable for women to wear kippot. I’m sorry if it offends you.”

“Okay. I didn’t realize you were Jewish.” She explained while I was puzzling over who else would wear a yarmulke, “I thought you were a Catholic kid setting a new trend.”

I forced myself not to laugh at the idea of me of all people starting a fad, wary of losing this belligerent stranger’s precarious goodwill. Then I noticed something strange about her pendant. The area where the two triangles of David’s shield met, usually empty, cradled a cross. Before I could control myself, I asked, “Why does your Star of David have a cross in the middle?”

Oops. The combative glare returned full strength. I put a sweatshirt rack between us and tried to appease her with the sacrifice of polyester fleece to substitute for my sheepish self. “I’m sorry. I’ve just never seen one like that before.”

She must’ve recognized my harmlessness, as she relented and revealed how she’d been brought up Pentecostal and recently learned that her ancestors had been conversos, Spanish Jews baptized into the Catholic Church to avoid being evicted in 1492 with their co-religionists. More than a bit defensively, she declared that while she hoped to incorporate Jewish traditions into her religious practices, she wouldn’t go so far as to spurn Christ and his Gospels. “After all,” she proclaimed with zeal as militant as it was messianic, “Jesus was Jewish.”

That conversation lingers in my memory, but not just because of the dramatic confrontation between Our Pacifist Hero and the Rabid Evangelical Titan. It also embodied the potentially unifying—but often divisive—role in interfaith dialogue played by the figure of Jesus. “Jesus was Jewish after all,” that representative of the Yarmulke Police had said. But what did that mean to her, to me, and to believers (and non-believers) who have appropriated his image, from medieval Norse converts who turned him into a tow-headed warrior to young people who sport his image on T-shirts as if he’s the lead singer of a boy band?

I’m not the first to notice how people devote more energy to fashioning gods in their own image than in seeking out the divine likeness in their fellow human beings—sweaty, neurotic, and lovably flawed as we are. Still, Jesus as the human face of God seems particularly prone to this treatment. This tendency probably stemmed from the universalist approach Christians have taken ever since the Apostle Paul started spreading Jesus’ message to his non-Jewish neighbors. For a faith committed to the siblinghood of humanity, and sharing the faith with as many brothers and sisters as possible, it made sense to detach the figure of Jesus from the particulars of his time, place, and culture. Missionaries to the Irish represented Jesus as a plaid-clad Celt plying the North Sea in a coracle; missionaries to China depicted him sharing rice, not bread, with his disciples at the Last Supper. Removing the culturally specific trappings from Jesus made it possible for the faith to appeal to everyone. It underscored the notion of Christ as Everyman at the same time as he was Son of God.

One negative result of this distancing of Jesus from his Jewish milieu was that over the centuries since the Gospels were written, anti-Semitism was born and flourished in Christian communities. In some of the Christian Scriptures, while Jesus is never labeled outright as Jewish, his enemies are both the hereditary priesthood that continued in power until the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. and the rising rabbinic group, interpreters of religious law. The narrative of events leading up to his crucifixion includes a scene where a mob jeers at him, calling for his death, and they’re labeled not a rabble, but “Jews.”

Jesus’ original followers may have presented matters in this way to eschew narrow sectarianism (those who proposed limiting the growth of the Jesus Movement—not yet a new religious tradition—to their fellow Jews versus those who advocated sharing Jesus’ message with all people). The presentation also stems from sectarian disputes that were a consequence of the brutal Roman war against Jews in the years around 70 CE and the destruction of the Jerusalem temple—when Jews were grappling with different ways to replace the temple (while most Jews took the route of synagogue-based rabbinic Judaism, Jewish followers of Jesus conceived him as the replacement). Hundreds of years later, though, that presentation of Jesus versus “the Jews” became the inspiration for oppression, from discriminatory laws prohibiting Jews from farming or being guild members (limiting them to despised jobs such as money-lending) to sprees of genocide that erupted every Easter season, when the destructive myth of Jews murdering Christian children inflamed anew the superstitious rage of the ignorant and sparked genocidal violence from pogroms to the Holocaust.

The degree to which Jesus’ Jewishness is celebrated or denied, and the unintended consequences of the canonical Gospels’ account of Jesus’ ministry, took another personal turn when I played one of his disciples in a local production of Godspell alongside my husband, Seth Goldstein (who played Jesus) and our friend Bob Goldberg (who played John the Baptist and Judas). A product of the hippie era, Godspell offers audiences a progressive, activist Jesus who collides with the Establishment of his time. His antagonists thrive on admiration for their public displays of piety, but they do not represent Judaism as a whole. Conversely, Jesus’ Jewishness is presented explicitly: the Last Supper is a Passover Seder, and he recites the Hebrew blessings over bread and wine.

On the other hand, the musical does not question the common misperception of the Pharisees as stuffy representatives of entrenched religiosity. (Ironically, the Pharisees actually represented a liberal strand of rabbinic tradition that shared much with Jesus’ philosophy.) Friends who came to see the show reported afterward that the distinction between these Pharisees and Judaism as a whole was too subtle for audiences reared on the long-unquestioned assumption that Judaism represents at best a tradition of spiritless observance rendered obsolete by the Christian dispensation, and at worst as the force chiefly responsible for Jesus’ death.

Jewish-Christian dialogue has come a long way, but it’s also challenging to get around the fundamental difference between the two faiths: for many Christians, Jesus was the one we all were waiting for, while some Jews are still waiting for someone else, and others believe in a messianic age rather than an individual messiah or, in the words of the civil rights movement, “We are the ones we have been waiting for.” On this question—the cause of so much misunderstanding and violence—we must peacefully agree to disagree.

So what does the figure of Jesus, Jewish teacher and Christian savior, mean to me? I can’t speak for my co-religionists and wouldn’t try (it’s not for nothing that the old saying goes, “Two Jews, three opinions”), but here’s my approach, which some others of my temperament and progressive inclinations share. I imagine Jesus as a feistier brother of Buddha: fiercely committed to serving the most disrespected members of his society, rhapsodically in love with life, quick to become angry at injustice and intolerance and just as quick to laugh at a friend’s joke. While I don’t share the beliefs of some Christian friends in the divine aspect of Jesus, I believe in a Jesus who was a model human being, not because he distanced himself from the human condition but because he immersed himself fully in it and showed other human beings how to realize our fullest capacities, or in Buddhist terms, enlightenment.

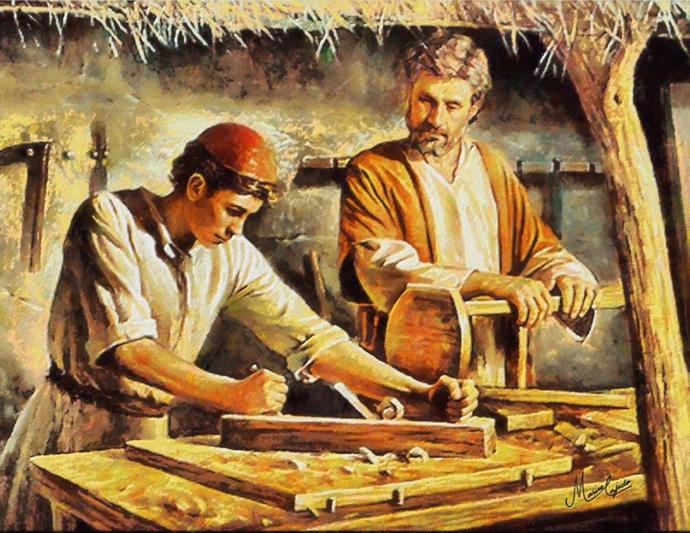

Whenever a movement, religious or otherwise, centers on a single charismatic figure, it’s inevitable that someone’s going to turn him or her into a hybrid of a superhero and a rock star. I’ve seen this Jesus. My imagined Jesus is a humbler figure, like my copy of a woodcut I love, showing him surrounded by the tools of the carpentry trade, wearing a protective apron and working at his bench. I imagine him stepping around curls of wood shavings, hoisting a pint at the local pub with his disciples (fishers in cable-knit sweaters), playing a first-century form of soccer with the neighborhood children and, because he’s a Jewish Jesus after all, engaging in that wonderful custom of celebrating and sanctifying every aspect of life with a prayer.

Braver than I am when confronted by the guardians of propriety who have shouted others into line in every era, my Jesus would also wear a kippah in a Catholic university bookstore.

What a lucid and compelling story!

Many of us have been smacked in the face by religious zeal. Sometimes the zealot seems driven by a genuine desire to share their spiritual discoveries. Other times they’ve been trained to recruit converts to a particular faith, or soldier some theological doctrine. Maybe some believers are extroverts who’re prone to leap at any topic that enables them to assert their personalities. The impulse could ride on anything, I suppose — maybe their favorite rubik’s cube strategies, or the best way to make caramel apples, or the coolest set designs for hobby railroading.

Whatever the reason, this habit can suck the air out of our conversations. We need breathing room to kindle real relationships.

Here’s a little tale about a turn-around. Recently a customer in Jupiter’s Books started to pick up a new print edition of the Upper Left Edge. Then he saw the cover and backed away. He recounted an experience when some “Jews for Jesus” infiltrated a weekly Talmud study group. When they finally came out, guns blasting, it wasn’t pretty.

I encouraged him to read your piece, Margaret, and asked him to please let me know if anything in our paper smacked of that kind of assault on spiritual sensibility. We exchanged some ideas and information, and he bought a book. Hopefully he’ll come back to visit the shop, and over time we’ll become friends.

Watt, this is a perfect description of the “converter” mentality that I find challenging, from both sides of the conversation–when talking about an issue I feel passionate about, such as the natural environment, I work on listening and speaking with mindfulness so I don’t turn into that conversation-stopping zealot!

Perhaps the key is to speak from the heart but not to turn one’s heart into a bulldozer, flattening all other hearts on its drive to salvation, transformation, or whatever else the person is looking for, spewing the airborne pollutants of judgmental words as it goes. It’s one thing to love, to be devoted, to some cause; it’s another when one’s devotion gets in the way of loving one’s fellow beings–loving them enough to allow them their own truths, as flawed and groping as any human truths can be.

Thank you for the beautiful words and the chance to reflect.

Oh Margaret, i so love your writing and i so love this piece. ” I imagine Jesus as a feistier brother of Buddha”, it’s honey, pure honey…Thank you for this beautiful perspective and the weaving of your words….

Yay, Vinny, I’m so glad my piece–and my picture of Jesus–resonated for you!

Wouldn’t it be cool to arrange a Jesus-Buddha soccer match? The fans go wild…

” I imagine him stepping around curls of wood shavings,”or” playing a first-century form of soccer with the neighborhood children” is an image of Jesus that i love to come back to, and Always makes me Smile…

Me too! What’s the use in being fully human and fully divine unless you can have fun with both states of being? (And that goes for all of us…)