This isn’t a review as much as a post-viewing reflection: free thoughts stirred into questions and connections. It’s better read after viewing the film, but there’s this trailer if you haven’t yet.

********************

Steven Spielberg combines the best elements of his past political films like Amistad, Schindler’s List, and Munich in the new drama-thriller Bridge of Spies. His chiding examination and partial rebuke of America today begins with a question framed by his camera in the first shot.

Who are we?

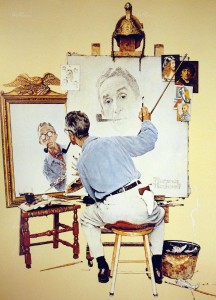

The movie opens on the back of an unknown man. To his left is a reflected image of his face in the mirror. To the right, a self-portrait still being painted on an easel. Three views of the same man. Which one is the right one? It is a sly nod to Americana, copying the self-portrait of famed painter Norman Rockwell, of whom Spielberg is a great admirer and collector. But it’s more. In opening Bridge of Spies with this quintessential American image starring a Soviet spy, Spielberg sets up his theme: who is the spy? And, more generally, who are we as humans? As Americans today?

The film offers many more answers than three. We’re prisoners — Abel, Gary Francis Powers, the student. By that nature, we are confined, with freedoms stolen. We are also foreigners: ones that freedom must be negotiated for. We are negotiators. As Donovan says, we are who we are because we’ve agreed on a book. The Constitution is one of the books. The Bible is another. And when agreeing on a book there are many shades of gray and complications that have to be maneuvered. Negotiated. We are honorable spies. Serving faithfully and fearlessly for a high cause and able to recognize that in another. Able to recognize humanity beneath job description. We are weak with foibles — as in Donovan having a cough and sneeze, not even a coat, vulnerable — and yet powerful. Not even as an official representative. But powerful. Able to say ‘This is how it’s going to be,’ and to have the CIA, the KGB, and the East German government all agree. On the word of one man who never wavers in what could be seen as an unreasonable request.

We are weak and yet we are strong. We are ordinary, aspiring to our work, and yet capable of the fantastic. And not just capable of but aspiring to, as in Abel’s Russian phrase which means ‘Standing Man’, the man who stands after getting repeatedly knocked down.

The Man Who Stands. The movie makes me think of another man who stood. On a cross as nails ripped through his feet. He had to negotiate and exchange. But he was the exchange. And in Gary Francis Powers crossing that bridge I see myself: earnest, broken, arrogant, a tear coming down my cheek, disbelief at seeing a friend. I see myself freed from confinement. I see myself saved. What have we been given? Spiritually, what freedom have we been given by the one who’s walked us over the bridge of spies?

Politically, what freedom have we been given? The freedom to climb fences without being shot. The freedom not to have walls built down the center of our streets. Not to have one side of our city bombed while the other side thrives. And yet, have we not done the same? Do we not build walls in Mexico? Do we not threaten those who would cross it for a better life? Are we not content with squalor on one side and privilege on the other? Are we proper stewards of this freedom? Spielberg is reminding us of our enemies and the things we have fought against in the past. And he’s gently holding up a mirror, painting, and filmed image to say ‘Do you not see, do you not see we do the same today?’ Maybe he would not say the ‘same’, or use the word ‘same’, for he is after all not a lecturer or an orator but a filmmaker. So what he gives us are not definitions but images. Images to evoke and characters to react.

Is the film’s answer that we are multi-faceted? The cough and power? The weakness and strength? The mighty government and one man? People of the book and negotiators of the lines within the book? Yes. We are all these things.

And…so are our enemies. One could argue in the humane treatment of the Soviet spy, in giving him the quintessential pose of an American icon to start out the film, that Spielberg is honoring our enemy as very much like us. He accords him respect. Think of that name now, the name of the spy. He’s ‘able’ to stand for his country. He’s also ‘Abel,’ the son of Adam preferred by God and betrayed by Cain. Donovan accords him respect. Though he is what today would be called a terrorist. He is the man we have locked up in Guantanamo. He is the man we have waterboarded in the wake of 9/11. He is the man we continue to hold in secret prisons as part of the CIA’s rendition program. That man still exists. That man is not accorded the respect James Donovan in Bridge of Spies accorded ‘his’ man.

Who are we? Why, we’re reluctant to claim others as our own. As Donovan says in the lounge, ‘He’s not my man.’ Continually, he repeats it. ‘He’s not my man.’ And yet, as he compares notes with Agent Hoffman later, he admits to being Irish and pegs Hoffman as of German descent. We may be reluctant to call the others our own but we are the others. We were the others. We have been the others. And Spielberg seems to be showing us we still are the others. We still are our own enemies. We are capable of doing that which we have fought against for decades.

In this gentle rebuke of America today that Spielberg offers through Bridge of Spies, is there hope? There is. Not in the largeness of government. Not in the suits and sedans. Not in the tricks and technologies. All of these things in this film seem mere props. Center stage are the humans. Center stage is an ordinary American working in insurance of all things. Is there hope? There is. Hope for an ordinary American to aspire to the fantastic. Hope in a man from another country stirring him to faithful dedication through his own story, filmed in one take, where international borders are lowered, life positions and political stances are set aside, and two human beings connect on a level of what it means to be a ‘Standing Man.’ What it means to be faithful. What it means to be loyal. What it means to be dedicated.

And, at the end of all of this, it’s as if Spielberg is asking us that very question. Who are we? Are there any among you, my movie audience, still willing to be the ‘Standing Man?’ Are there any of you willing to put your life on the line to negotiate for others lives? To be a Schindler? To be a Donovan? Are there any of you willing to face where your own country might be going wrong and to do your job as an ordinary one aspiring to the fantastic to change it? Or perhaps such language is too lofty for Spielberg’s conceits in this film. As James Donovan says it, he’s just doing his job. Perhaps that’s part of Spielberg’s admonition: he wants us all to do our job. And our job is to be an American. Our job is to be honorable. To live by the book. To respect our enemies. To appreciate our freedoms. That’s our job.

In Bridge of Spies, Spielberg asks if any of us are still ‘Standing Man’ enough to do it.

And question not only who we are, but our leaders, the book, honor, why our enemies are such, and the very concept of America. That is also our job. I haven’t seen the movie yet, but I hope Spielberg got that in there also. That said, I must say, Rick, that was an amazing “review”. Your writing keeps improving, and that was just for the opening shot! Great job!

Merci beacoup, Rabbi Bob. I’m sure you would have a hearty inner dialogue with this film were you to see it. I won’t write about this, but it’s an interesting companion piece to STEVE JOBS, which I saw last night. Two different worlds. And yet both telling us something about greatness. Or what’s worthy of giving one’s life for. I was interested by Jobs, but I’m haunted by Bridge and may go back to see it again.