“I’m a dangerous man, Will.” A year ago, Dad might’ve grinned and inflected these words with Irish mischief, but Parkinson’s disease has scoured his face to expressionlessness and hearing loss has blurred the syllables. “But do you know what’s the most dangerous of all?” Dad takes my brother’s arm. His fingers, too awkward and swollen to hold with anything less than the entire hand, can startle with their strength, especially as he struggles to stand up unaided. He leans in, confiding, “Angels. There’s nothing more dangerous than the angels.”

Dementia is cruel, capricious, and chimerical. My father, a retired classics scholar and special-education teacher, has carried with him his impressive vocabulary, but it’s difficult to determine if he wields his words with intent or if they rise to his lips like images in dreams, luminous and haunting but not always sensible. His statement about angels could convey insight, profundity, even humor…or it could be a patchwork assembled from memory-scraps. Listening to him speak, you witness a brilliant mind in ruin, transcendence, or both. After a year of caring for him as Parkinson’s disease has worn away his ability to care for himself, I still don’t know.

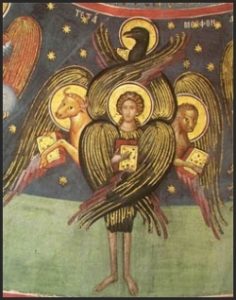

When I was a child, I imagined angels like the ones in sentimental postcards, those romanticized winged guardians walking alongside a blond, middle-class boy and girl whose aggressive normality rendered them as iconic as their protector. Yet the angels I read about in various sacred traditions were awesome in the old sense: beautiful and frightening. Somewhere I recall reading that angels, unlike human beings, were not gifted with free will. (This notion did not explain how Lucifer managed to rebel against heavenly rule.) They were magnificent engines of God, praising their maker and carrying out divine instructions.

A person under dementia’s sway resembles these angels: compelled rather than choosing, mighty and powerless, dangerous to those who love them and remember them in their full humanity, before they started approaching the great mystery at life’s borders.

Where do my father’s words, the ones that sound like prophecies, come from? Are they the random driftwood of a splintering mind, or are those splinters cracks through which light, both sacred and difficult, can shine?

I can’t always determine what he’s cobbled together from his bruised memory and what he’s using his still keen intelligence to assemble from the information his fading senses send him. This morning, he tried to drink his bagel with a straw. Another day, he pointed to a fallen tissue and said, “The hotel has nailed the bill to the floor. Can you get it for me?” (He has called his house a retreat center, a library, a museum, and a hotel and, after filling it with books, furniture, and memorabilia for four decades, I suppose it can pass for all of these.)

Sometimes his mistaken impressions worry him. I was changing his sheet one day when he begged me to stop, insisting that the sheet was “my brochure about milking, which I have been trying to find for some time.” When I asked him about it, he explained, “It tells you how to milk the cow, but not where,” a tidbit he imparted to me as if dispensing millennia-old wisdom. (By “where,” did he mean the location of the milking parlor or the udder?)

There’s sense in these gnomic utterances. A lifelong city-dweller, Dad was fascinated by country living, from organic farming to traditional furniture-making methods, although he spent more time studying these subjects in books than planting vegetables or caning chairs. Thus, it’s not unprecedented for him to collect brochures on milking cows. Another day, my mother was helping him to eat his lunch and, when she took up another spoonful, Dad said, “I’ll give Jere his turn.” Once Dad had told me about his childhood during the Great Depression, when his father gathered the children in a circle (whether around a table or on the floor I don’t know), put a soup can in the middle, and offered a spoonful to each child in turn, accompanying the scant meal with humorous commentary. It’s possible that after all these years (and with his brother having predeceased him a year ago), he was offering his next mouthful to his younger sibling.

If it’s challenging to decipher the reasons behind an individual statement, it’s an even greater conundrum to determine what caused my father to develop this condition, especially with the associated dementia (which affects only a minority of people with Parkinson’s disease). Parkinson’s is a common but mysterious condition, affecting about one in 100 people in the United States. Its origins are uncertain: it’s not genetic, which suggests an environmental cause. In a world awash in toxic chemicals, it’s difficult to identify a particular trigger. Dad was a teacher; he does not remember experiencing any significant toxic exposures, other than having lived in New York City his whole life. He has never smoked, he did not drink alcohol to excess, he was an organic-food proponent, and he exercised moderately; he also has no other chronic ailments. So what has brought him to this pass? In the absence of an identifiable cause, it’s understandable why many people take refuge in metaphysics for answers.

Being separate from the angels’ realm, and hence receiving whatever messages the universe sends in forms as blunted and obscured as my father’s communication, doesn’t stop human beings from attempting to find meaning in — or impose meaning on — whatever happens to us. We ask why one person reaches her nineties with faculties intact and strength and reflexes diminished but not vanished, while at the same age another ceases to recognize his spouse and home, thinks he is 19, and cannot dress or use the toilet unassisted. Is it evidence of divine favor that a man gets to hike each morning in his favorite park until the day he dies at age 94? What sins or karma can a lady possibly atone for by living the last five years of her life unaware of who she is, where she is, and what she’s doing? What life lesson can she learn when her mind has come undone and she can’t reflect on her condition?

These speculations lend themselves to simplistic answers that lay the blame for what happens to us on our prior actions, whether in this lifetime or in another. Such answers don’t leave room for change-making. After all, why work to eradicate a life of poverty and discrimination if this is our well-deserved fate? Why strive to create justice for all, including humane treatment of elders (regardless of disability status and cognitive capacity) and those who care for them, if losing one’s powers for thought, movement, and independent living is one’s rightful punishment? While I champion every effort we humans make to understand our condition, I don’t consider it fruitful to ask what “crimes” our misfortunes are meant to make us pay for, including the misfortune of physical and mental decline many experience at life’s edge. I’d rather ask how those of us who are (at least temporarily) abler can create a world where people with disabilities can receive assistance with dignity, in accordance with their own wishes and their loved ones’, and without discrimination and adverse financial repercussions.

My parents have always been adamant about remaining in their home for life. They have friends who are pleased with their assisted-living facilities, but this is not their preference. Yet the prevailing elder-care paradigm assumes that by default an elder will leave her home for assisted living or an extended-care facility when she can no longer perform daily activities without help. This model is the basis for medical insurance outlays for elder care. This is what many folks, at least in the United States, assume will be their lot, to judge from all the offhand comments about one’s children picking out one╒s nursing home. As with many people who have Parkinson’s, my father underwent a rapid decline: he suddenly went from being mentally intact and caring for himself (even if he shuffled along, taking a half-hour to go from the dining room to the bathroom) to requiring a wheelchair to get around and being disoriented in his home.

He also started falling several times a week when trying to move from bed to wheelchair or wheelchair to toilet. It didn’t help that he has severely impaired vision and hearing. My husband and I had been caring for him for a month, cooking for him and doing his errands, when he experienced this precipitous loss of function, and we realized that he needed professional in-home care, so we took him to his physician for evaluation.

The doctor was sympathetic and recognized his situation immediately, but Medicare — his primary insurance — only paid for six weeks’ physical and occupational therapy and two hours’ caregiving three times a week. Eventually, my mother found a wonderful private caregiver in the neighborhood to help him each morning and evening, but Mom has depleted her pension and life savings to afford this. It’s unconscionable that our elected officials don’t consider it worthwhile to spend public money on guaranteeing our elders their preferred living and care arrangements and affording their caregivers a living wage without bankrupting the elder and his family.

Another angel-related tradition I’ve come to cherish is the Jewish legend of the Lamed Vav, the thirty-six Tzadikim (just people). These righteous individuals, just by their presence, uphold the world — and the delightful twist is that they don’t know who they are, nor do we. Therefore, we’re enjoined to treat everyone as if he or she is a Lamed Vavnik. Maybe that kid fiddling with her Play Station on the park bench next to you is one. Maybe the old man who’s lost on his own street corner is another. Angels are dangerous, especially when we don’t recognize and acknowledge them, when we cease to treat ourselves and others like the angels they, and we, all are inside ourselves, just waiting to release our light.

Leave a Reply