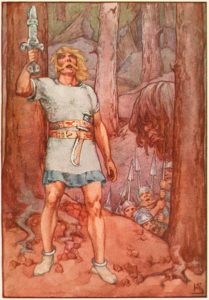

Illustration of Beowulf

A Book of Myths (1915)

by Helen Stratton

The Venerable Bede’s eighth-century Ecclesiastical History of the English Peoples describes an encounter between Christian missionaries and England’s “barbarian” ancestors. One glimpse of the tall, sturdy Germanic warriors prompted a missionary to exclaim that the heathens must be angels. Someone corrected him, “They’re not angels; they’re Angles,” “Engla,” from which the words “Englalond” (England) and “English” evolved.

By the Middle Ages, England had become a multi-ethnic society: Britons, the original Celtic inhabitants; Angles, Saxons, and Jutes, who began migrating from a region below Denmark in the fifth century; Vikings from Scandinavia, who invaded and then settled from the eighth to the tenth centuries; and Norman peoples from France, arriving with William the Conqueror in the eleventh century.(1) The period’s literature reflects this polyglot composition. Beowulf was written in Old/Anglo-Saxon English between the seventh and ninth centuries and interweaves mythology and Scandinavian history.(2) Bede’s History is an early attempt to define English peoplehood. Other semi-histories like Nennius’ Historia Brittonum and Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittaniae represent efforts to supply medieval English people with both a coherent past and a legendarium, whether the latter is the Arthurian cycle or the Iliad, with Trojan refugees establishing a new empire on British soil.(3)

Nineteenth-century nationalism rekindled interest in these stories. Scholars and political figures claimed Beowulf and other works as Northern European epics, whether tied to national groups in the making (as with Grimur Thorkelin’s 1814 edition of Beowulf, which the editor-translator claimed as a Danish saga) or to a nascent pan-Germanic identity.(4) Anglo-Saxon “angels” became ideals of Germanic warrior manhood: loyal to their brotherly bands, stoic in fighting and loving, and noble in death. They were recruited posthumously into the army of white supremacy, incorporated into a mythology that canonized “Nordic” peoples as the angels and supermen ordained to dominate the earth. Their strapping but clean-cut image inspired the early twentieth-century eugenics movement and culminated in the atrocities of Nazi Germany.(5)

Because of the vile use to which Bede’s barbarian angels have been put, it’s understandable why many people are uncomfortable studying them. So why, in my senior year of college, did I waver between applying to rabbinical school and a PhD program where I’d focus on Old and Middle English Literature? What attracted a nice Jewish girl to Beowulf? Can the study of Northern European cultures ever be free from the shadows of nationalism and racism?

To address the personal side first: J.R.R. Tolkien made me do it! I’ve always been attracted to deep time, to origin stories and misty beginnings. Discovering first the Grail legend when I was eleven and then The Lord of the Rings when I was thirteen answered these longings and also intensified my thirst to learn more. I found that Tolkien’s magisterial work had been inspired by his expertise in medieval English, Norse, and Icelandic languages, and my desire to delve into the literature he loved caused the PhD program to win out over rabbinical school. During the ‘90s (I received my PhD in 1997), cultural studies across academic disciplines prompted scholars to question Eurocentric biases. My love for medieval legends as origin stories became a more nuanced appreciation for the medieval period as a time when both cultural/religious pluralism and intolerance flourished, when fanciful stories about voyages to other lands revealed insecurities about “otherness” in the guise of dog-headed monster-people.

Eventually my own otherness confronted me in a medieval mirror. Medieval anti Semitism is an instructive and chilling example of how a majority culture demonized a minority. Jews began migrating to England in the seventh century, but they were still so few in number that not many Christian English-people had personal encounters with one. In the absence of real Jews, “the Jew” became a symbol for difference (of a sinister, despised kind) at a time when “Anglish” people were beginning to define themselves as a distinct culture.(6) Medieval writers’ fascination with and fear of difference is a rich area for investigating – and is more relevant than ever after the 2016 election, when long-simmering hatreds have surged back to the surface, surprising those of us who’d hoped a postracial society was on the near horizon.

I believe rejecting Northern European studies as an academic discipline because of racist associations would be a mistake, but so would promoting the field without confronting those associations. We need a whole history — devils, angels, and ordinary mortals in between, those who cooperated, those who resisted, and those who consented with silence. For centuries, “history” has meant European history, and that unjust imbalance must be rectified. Not only history but the future also belongs to the world’s cultures, and European hegemony must end. Reclaiming Northern European studies from abuse by racist agendas should be part of this process. If reputable researchers and academic programs reject the discipline as abstruse, irrelevant, or tainted, we’ll be abandoning it for the white supremacists to claim as their own.

1 Beowulf, a Dual-Language Edition, Chickering, Howell D., editor and translator, New York: Anchor Doubleday, 1989: 259.

2 Chickering 247.

3 Chickering 259.

4 Frantzen , Allen and Niles, John D., editors, Anglo-Saxonism and the Construction of Social Identity, Gainesville: U of Florida P, 1997: 8.

5 Frantzen and Niles 8-10.

6 Scheil, Andrew P., In the Footsteps of Israel: Understanding Jews in Anglo-Saxon England. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2004.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.